Dionysus stands as one of the most intriguing figures in Greek mythology, embodying the dual nature of joy and chaos. Known as the god of wine, fertility, and festivity, your exploration of this deity reveals a complex character connected to both life’s pleasures and its unpredictable forces.

As the son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, Dionysus occupies a unique place among the Olympian gods, having traversed the boundaries between the mortal and divine realms.

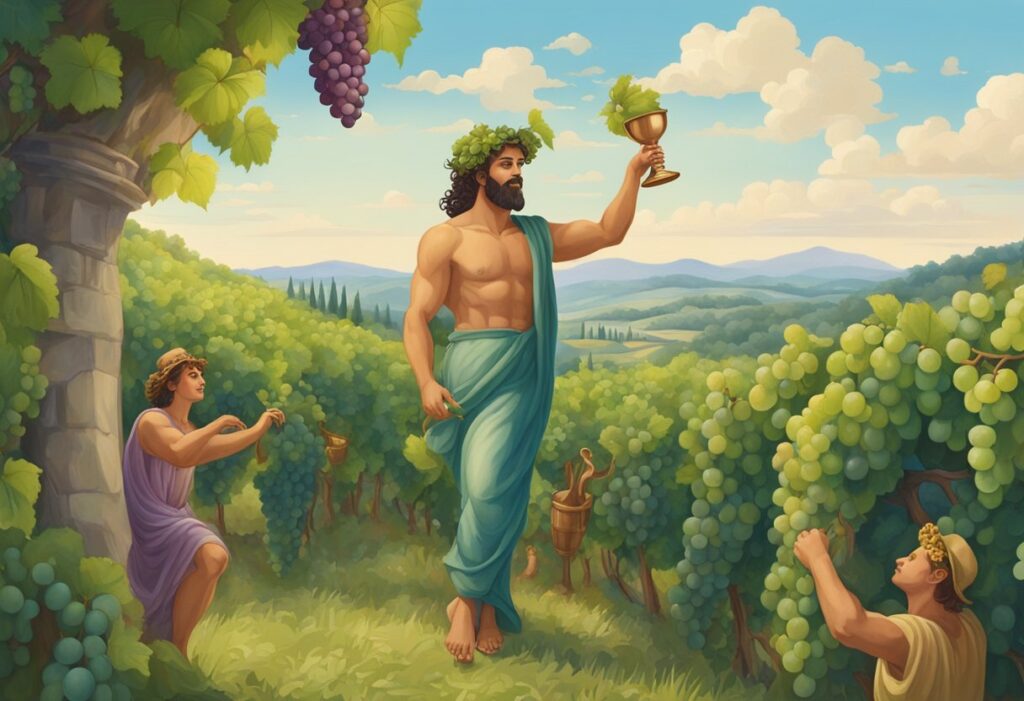

Your understanding of Dionysus is enriched by recognizing his symbols, such as the grapevine and thyrsus, which encapsulate his influence over viticulture and the intoxication that can lead to both euphoria and madness.

The elaborate rituals and festivals dedicated to Dionysus, like the iconic Dionysia, signify your appreciation of his significance in Greek culture, echoing the enduring human fascination with the ecstasies and excesses that he represents.

Key Takeaways

- Dionysus is a multifaceted deity known as the god of wine and symbol of life’s contradictions.

- He is celebrated with symbols like the grapevine and through rituals that reflect his cultural impact.

- Dionysus’ heritage and revelries illustrate the close ties between divine myth and human experience.

Origins of Dionysus

The mythical narrative of Dionysus is a tale of divine birth and unique rebirth, intertwining his existence with the realms of gods and mortals.

Zeus and Semele

Dionysus is the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Semele, a mortal daughter of Cadmus of Thebes. Their union was clandestine due to Zeus’s marriage to Hera. When Hera discovered the affair, she visited Semele disguised as an old friend and tricked her into asking Zeus to reveal his true form. This request led to Semele’s demise, as mortals could not look upon gods in their true form without dying.

Birth and Rebirth

Despite the tragedy, Zeus rescued the unborn Dionysus by sewing him into his thigh, earning Dionysus the tag ‘twice-born’. Later, Dionysus emerged from Zeus’s thigh as a rebirth, marking his entry into the world of gods as a deity who would straddle the lines between mortality and divinity. His birth is unique among the gods, combining the mortal and the divine.

Attributes and Symbols

Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and revelry, is consistently associated with symbols that reflect his influence over viticulture, festivity, and wilderness. Each symbol provides insight into his complex character and varied domains.

The Vine and Wine

The grapevine is Dionysus’ most iconic symbol, representing the cultivation of grapes for the production of wine—a drink deeply intertwined with Greek culture and social life. Ancient processes of winemaking connected to Dionysus show the significance of this beverage in rituals and daily life.

His festivals, such as the Dionysia, were occasions for drinking wine as a form of worship. Dionysus is also associated with ivy, a plant often depicted alongside the grapevine, symbolizing eternal life and resurrection due to its evergreen nature.

Thyrsus and Animals

Thyrsus, a staff wound with ivy and topped with a pine cone, signifies Dionysus’ power to induce frenzy and provide fertility. It was a common item carried by his followers, the maenads, during their ecstatic dances.

In the wild entourage of Dionysus, animals like the bull, panther, snake, and goat are symbolic companions. These creatures are embodiments of strength, freedom, fertility, and instinctual power that reflect the untamed aspects of nature and human psyche that Dionysus himself encompasses.

Worship and Festivals

Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, fertility, and revelry, was celebrated with both public festivals and secretive rituals. Your participation in these events was not only an act of worship but also a communal activity that bonded you with others in your society.

Dionysia

The Dionysia were a series of festivals held in honor of Dionysus. The most significant of these was the City Dionysia, which took place in Athens and boasted performances of tragedies and comedies—an event you might attend to enjoy theatrical innovation. It was a vital cultural festival that encouraged civic identity and participation.

Urban Dionysia

- Season: Spring

- Activities: Theatrical performances, processions, competitions

Rural Dionysia

- Season: Winter

- Activities: Smaller celebrations, dramas, and dithyrambic contests

Bacchanalia

Originally, the Bacchanalia were secretive wine festivities that you might have known about through rumors or private invitations. In Rome, the Bacchanalia were outlawed for their perceived excessive and immoral revelries; nevertheless, they were crucial for personal expressions of ecstasy and freedom.

- Characteristics:

- Secrecy

- Exclusivity

- Frequency: Originally monthly, then became a 5-day event

Dionysian Mysteries

The Dionysian Mysteries were rituals that offered you a more intimate and esoteric connection with Dionysus. These Mysteries promised a personal spiritual experience, one with symbolic actions that could lead to personal rebirth and transformation.

- Ritual Elements:

- Symbolic props: fennel stalks, ivy, wine, honey

- Actions: Dancing, intoxication, the revelation of sacred objects

Followers of Dionysus

Dionysus, the god of wine, festivity, and ecstatic celebration, commanded a passionate and fervent following. You’ll discover that his primary adherents comprised beings associated with revelry and wildness.

Maenads

Maenads, or Bacchantes, were the most zealous followers of Dionysus. They are often depicted as women in the throes of frenzy, girdled in fawnskins and wielding the thyrsus, a staff wrapped in ivy and vines. They embody the uninhibited spirit of Dionysus and were believed to roam the mountainsides, engaging in ecstatic dancing and other rites. The Maenads were central to the worship of Dionysus, illustrating the god’s power to liberate and induce divine madness.

Satyrs and Sileni

Satyrs and Sileni were male followers synonymous with Dionysian revelry. Satyrs are often described as half-man, half-beast, companions to Dionysus embodying the untamed forces of nature and indulgence. They played lyres and flutes, dancing with exuberant autonomy.

Sileni, older and wiser creatures, also followed Dionysus; they are commonly associated with the nurturing of the wine god in his infancy. The Satyrs and Sileni were fixtures in Dionysian processions, symbolizing the god’s association with fertility and the primal instincts that wine and festivities could awaken.

The thiasus, Dionysus’s retinue, often included nymphs and other nature spirits, all reveling in the god’s gift of wine and ecstasy. Your understanding of Dionysian worship would note these followers epitomize the liberating and intoxicating essence of the god they adore.

Dionysus in Greek Culture

As you explore Greek culture, Dionysus stands out as a multifaceted deity. His influence is pervasive, from the myths and literature that shape the fabric of Greek storytelling to the profound impact he has had on the arts.

Myths and Literature

Dionysus is often depicted in Greek myths as the god of wine, ecstasy, and madness. He represents not only the intoxicating power of wine but also its social and beneficial effects. He is a son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, making him a bridge between the divine and human worlds.

In literature, perhaps the most notable work is The Bacchae by Euripides, one of the great Greek tragedians. The play portrays Dionysus as a god of rage and vengeance, returning to Thebes to clear his mother’s name and punish the city for not respecting his divinity. You’ll find Dionysus to be a complex character, capable of bringing both joy and destruction.

Influence on Arts

In the realm of the arts, Dionysus’ influence is readily apparent. He was revered in the Dionysia, a festival of entertainment where many famous Greek tragedies were performed. His representations range from a bearded man to a younger, effeminate appearance in later arts. Dionysus is also associated with iconic symbols like the thyrsus, a staff twined with ivy and topped with a pinecone, and the grapevine.

Throughout Greek art, Dionysus is a testament to human emotion, from jubilation to sheer madness. His worship involved frenzied dances and rites that hint at his role in liberating his followers from self-consciousness and societal norms.

Alongside other gods such as Athena and Hermes, Dionysus had a unique place, defying conventional morality and encouraging his followers to embrace their instincts.

Interactions with Other Deities

In the intricate tapestry of Greek mythology, your understanding of Dionysus’s interactions with other deities, especially with Olympian gods, illuminates his complex role and relationships within the divine hierarchy.

Dionysus and Hera

Hera’s jealousy and scheming are infamous, and her interactions with Dionysus are no exception. You’ll find that Hera, Zeus’s wife, played a pivotal role in Dionysus’s early life. She tricked Semele, Dionysus’s mortal mother, into demanding to see Zeus’s true form, which led to Semele’s demise.

Despite Hera’s initial hostility, Dionysus later became one of the Olympian gods, which suggests a reconciliation, or at least an acceptance, part of the dynamic pantheon that included Hera herself.

Athena and Apollo

Dionysus also interacted with Athena and Apollo, both of whom were his fellow Olympians. Athena, known for her wisdom, likely viewed Dionysus’s domain of wine and ecstasy as contrary to her values of reason and strategic warfare. However, there were no significant myths of direct conflict between them, implying a level of mutual respect or at least a détente in their dealings.

In contrast, Apollo, the god of music and prophecy, shared more common ground with Dionysus through their association with the arts.

The two were sometimes linked in their patronage of the theater and had intertwined aspects of worship, for Apollo’s oracles and Dionysus’s rituals held equal importance in Greek culture. Their interaction signifies the harmony between the ecstatic and the rational aspects of both deities’ domains.

Roman Counterpart: Bacchus

When you explore the pantheon of Roman deities, you’ll find that Bacchus stands as the Roman counterpart to the Greek god Dionysus. Known for being the god of wine, ecstasy, and fertility, Bacchus was a key figure in Roman religion and was closely associated with the pleasurable aspects of life and the freedoms tied to coming of age and citizenship.

Roman Worship

Bacchus, also known to Rome as Liber Pater, was a deity celebrated for his influence over viniculture and male fertility. Your understanding of Bacchus should not be limited to the tales of cheer and revelry; he also symbolized the protection of traditions and the social order, particularly in the context of citizenship.

The Roman state’s relationship with the worship of Bacchus was complex, acknowledging his role and yet sometimes viewing independent Bacchanalia celebrations with suspicion, as these festivals could appear subversive.

Bacchus and Festivals

Bacchus was at the heart of several festivals in Rome, most notably the Bacchanalia, which were originally held in secret and only attended by women. These festivities celebrated the god through wine, music, and ecstatic dance.

Eventually, the Bacchanalia opened up to all, becoming a public festival, which showcased the extent of Bacchus’s influence. Yet, this inclusivity also led to stricter controls by the state, as the liberating and sometimes disorderly nature of these festivals caused concern among Roman authorities wary of their disruptive potential.

Symbolism and Influence

Dionysus, a figure of immense cultural significance, encapsulates themes of theater and tragedy, fertility and vegetation, as well as madness and ecstasy—each reflecting the diverse aspects of life and nature he influenced.

Theater and Tragedy

You might find it intriguing that Dionysus is closely linked to the origins of Greek theater. Ancient performances, particularly tragedies, were held in his honor, signifying not just entertainment but a complex blend of emotions and societal narratives. Events like the City Dionysia were festivals that celebrated his influence through performances that were both solemn and celebratory.

Fertility and Vegetation

As a god of fertility and vegetation, Dionysus was venerated for his ability to bring forth life from the earth—be it in the form of the vine that yields grapes for wine or the bountiful harvests that sustain communities. His role is a testament to the cycle of life and death, a concept embedded in seasonal changes and agricultural practices symbolized by elements such as the vine and ivy.

Madness and Ecstasy

The duality of Dionysus’s nature is perhaps most evident in his association with madness and ecstasy. These states were seen as divine gifts that liberated individuals from self-consciousness, enabling a form of spiritual communion on mountain retreats.

However, the line between divine madness and destructive mania was fine, underscoring the volatile aspect of his followers’ ecstatic worship. His influence here speaks to the transformative power of losing oneself in something greater—a principle deeply rooted in both ancient rituals and enduring cultural expressions.

Legends Beyond Greece

The worship and cultural impact of Dionysus extended far beyond the borders of Greece, influencing societies from Asia Minor to Rome. His myths and traditions adapted to local cultures, demonstrating his universal appeal as a symbol of wine, festivity, and rebirth.

Dionysus in Asia Minor

In Asia Minor, Dionysus was a well-established god, with his cult taking on forms unique to the region. You’ll find that Hellenistic cities in these lands often linked Dionysus with local deities, leading to a syncretism that made him an integral part of their religious life.

The city of Ephesus, famous for its Temple of Artemis, also had a strong following of Dionysus, showcasing the god’s importance in trade and cultural exchanges, particularly in the spread of viticulture and the use of amphorae in the wine trade.

Expansion to Rome

As the worship of Dionysus moved westward, reaching Rome, he became known as Bacchus. Romans adopted many aspects of his worship but with their own distinctive rites and festivals, like the Bacchanalia.

These festivals, initially structured around wine, agriculture, and theatrical performances, evolved into popular social events. Moreover, your understanding of the Roman adaptation of Dionysus cannot be complete without appreciating the role of wine across the empire.

The cultivation of vines and wine production saw remarkable growth, essential to both religious rites and daily life, as seen in accounts of wine in antiquity.

In these regions, the figure of Dionysus represented not just the frivolous joys of wine but also the cyclical nature of life and the possibility of rebirth and rejuvenation.

Through festivals, theater, and rituals, his legends remind you of the prevalence and continuity of Dionysian symbolism in the broader Mediterranean world. The deity’s versatility in blending with various cultural norms showcases his significant influence throughout diverse ancient civilizations.

Enduring Legacy

Dionysus has left an indelible mark on modern culture and art, intertwining ancient myths and rituals with today’s expressions of creativity and festivity.

Modern Depictions

You’ve likely encountered Dionysus in various forms of modern media. He is depicted in literature and film as a symbol of liberation and unrestrained indulgence, reflecting his mythological roots in wine, fertility, and ecstasy.

His stories often explore themes of resurrection and rebirth, resonating with audiences who appreciate the cyclical nature of life. This timeless connection can be seen in modern interpretations of plays and movies, where his influence extends beyond the confines of ancient texts.

Cultural Resonance

The far-reaching influence of Dionysus is evident not just in art, but also in cultural movements and modern practices. For instance, you can trace the spirit of Dionysian cults through today’s festivals that celebrate excess and freedom.

Mardi Gras and Carnival, while not directly associated with Dionysus, embody elements of the ecstasy and joy that characterized the Bacchanalia—the Roman festival in honor of Bacchus, the Roman counterpart to Dionysus.

Contemporary artists and thinkers often reference Dionysian elements to contrast with the structured and rational “Apollonian” attributes, highlighting a duality that is still relevant in your understanding of human nature and society.